1969: Student Protests at City College

“Support the Five Demands” served as the battle cry for City College students who seized the moment in the spring of 1969.

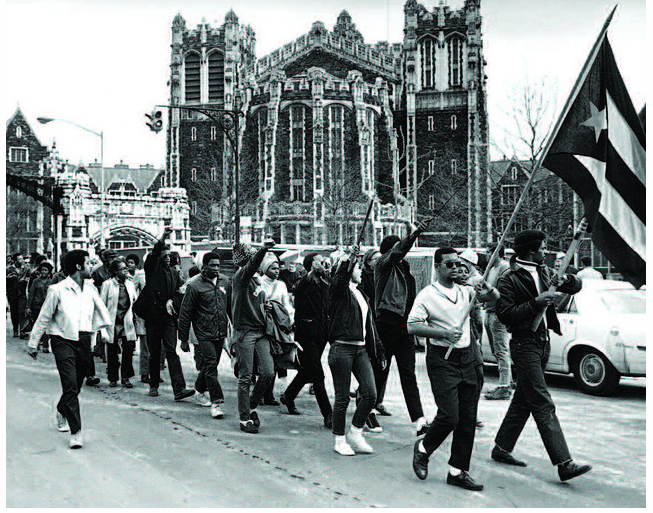

Photo courtesy of City College Archives

CCNY students, some of them members of the Puerto Rican Institute for Student Action (PRISA) demonstrate on campus after a meeting with administration and faculty members. Student at right carries a Puerto Rican flag.

Photo courtesy of The New York Times

City College President, Robert E. Marshak, lucidly described the mood of college campuses during that time:

Source: Virginia Tech

“The student unrest that overtook many campuses in the United States in the late 1960’s was fanned by growing opposition to the disastrous Vietnam War…. At the time, the civil rights movement—under predominantly Black leadership—which had received great impetus from the Supreme Court decision of 1954 (mandating desegregation in education) and was running a fairly independent course of its own, attempted to eliminate all perceived manifestations of institutional racism in the United States, including college and university campuses…. With the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, coming as it did when the opposition to the Vietnam War peaked (President Lyndon Johnson withdrew from the presidential race at about that time), campus confrontations clearly were to be expected. It is within this historical context that one must try to understand the meaning of the non-negotiable Five Demands presented to the City College administration by the Black and Puerto Rican Student Caucus at the time of its occupation of the south campus on April 22, 1969.”

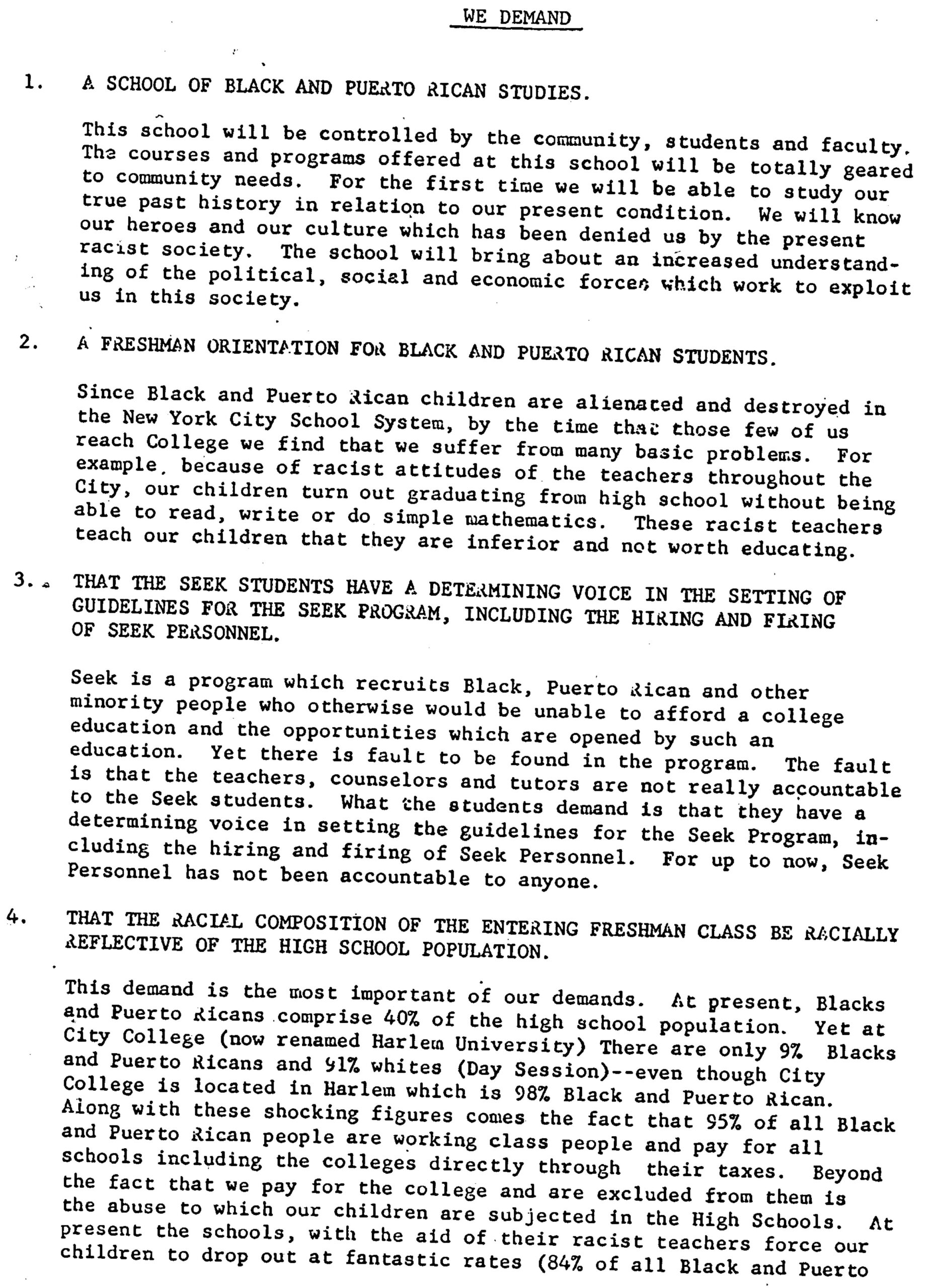

The Five Demands

In February 1969 proposed budget cuts, if implemented, would have eliminated the SEEK Program and frozen non-SEEK admissions. City College President Buell G. Gallagher threatened to resign if these cuts were approved, and more than 13,000 CUNY students rallied in support in Albany. Even with these actions, the university received $29 million less than it had requested. A chaotic, complicated, and often confusing course of events took place on campus during the following months. On February 6, 1969 the Black and Puerto Rican Student Community presented these “Five Demands” to President GallagherA separate school of Black and Puerto Rican studies.

ONE: A separate school of Black and Puerto Rican studies.

TWO: A separate orientation program for Black and Puerto Rican freshmen.

THREE: A voice for SEEK students in the setting of all guidelines for the SEEK Program, including the hiring and firing of all personnel.

FOUR: The racial composition of all entering classes should reflect the Black and Puerto Rican population of New York City high schools.

FIVE: That Black and Puerto Rican history and Spanish language be a requirement for all education majors.

Source: CUNY Digital History Archive

President Gallagher valiantly tried to negotiate these demands. He invited students to participate in the planning of Black and Hispanic studies programs and said that the Dean of Students would be re-examining the freshman orientation program to meet the needs of Blacks and Puerto Rican students. The President also pointed out that the SEEK director welcomed greater student participation by SEEK students in hiring guidelines, and that the School of Education had been revising and perfecting its curriculum and was inviting student participation.

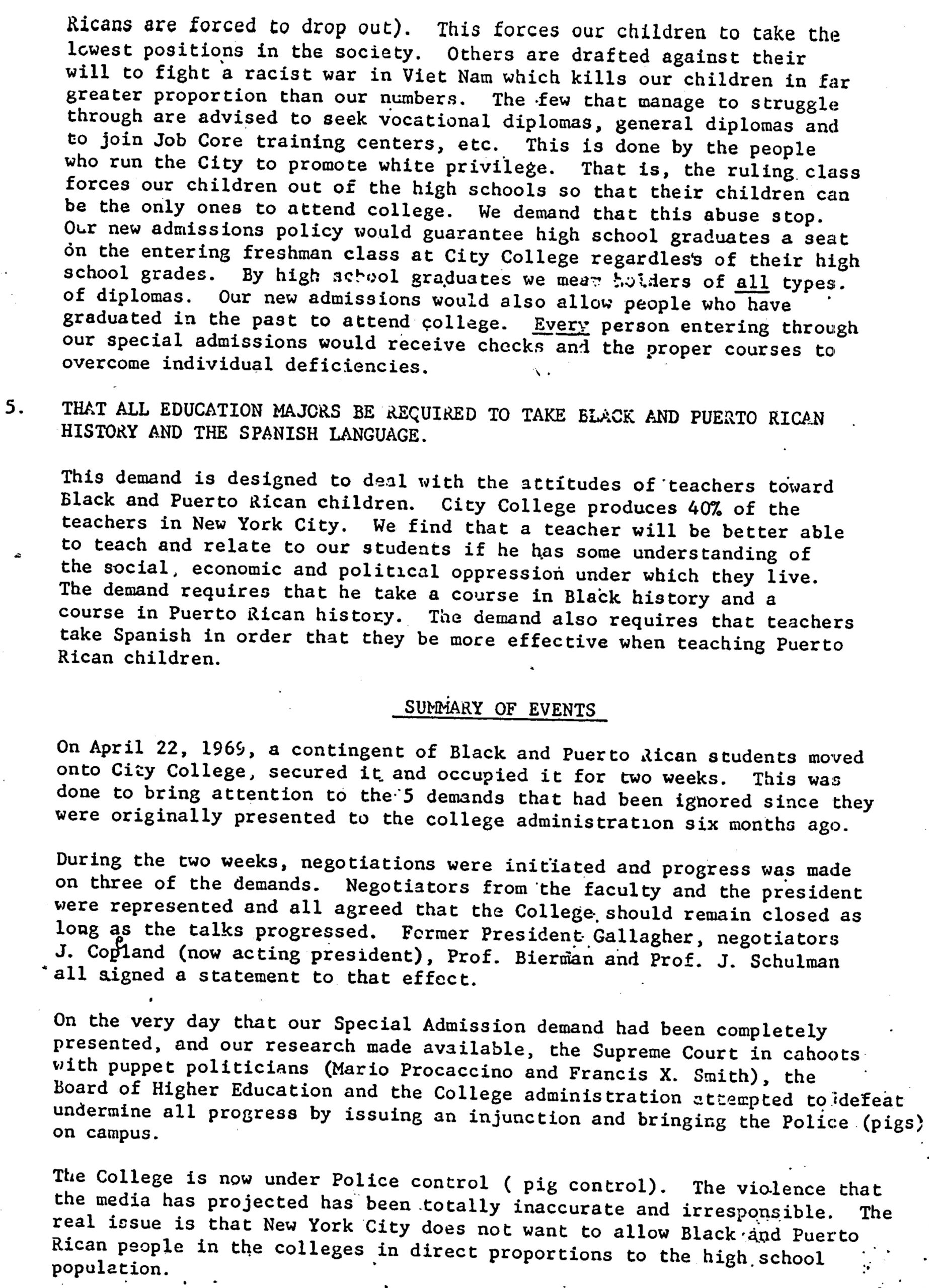

Photo courtesy of the New York Daily News

Many of the students were not satisfied with the President’s responses. The following week there was some rioting on campus. In a meeting with students in April, President Gallagher reported that a year of Spanish would be required for education majors as of September 1969, and courses in Black and Puerto Rican heritage would be incorporated into the offerings of the School of Education.

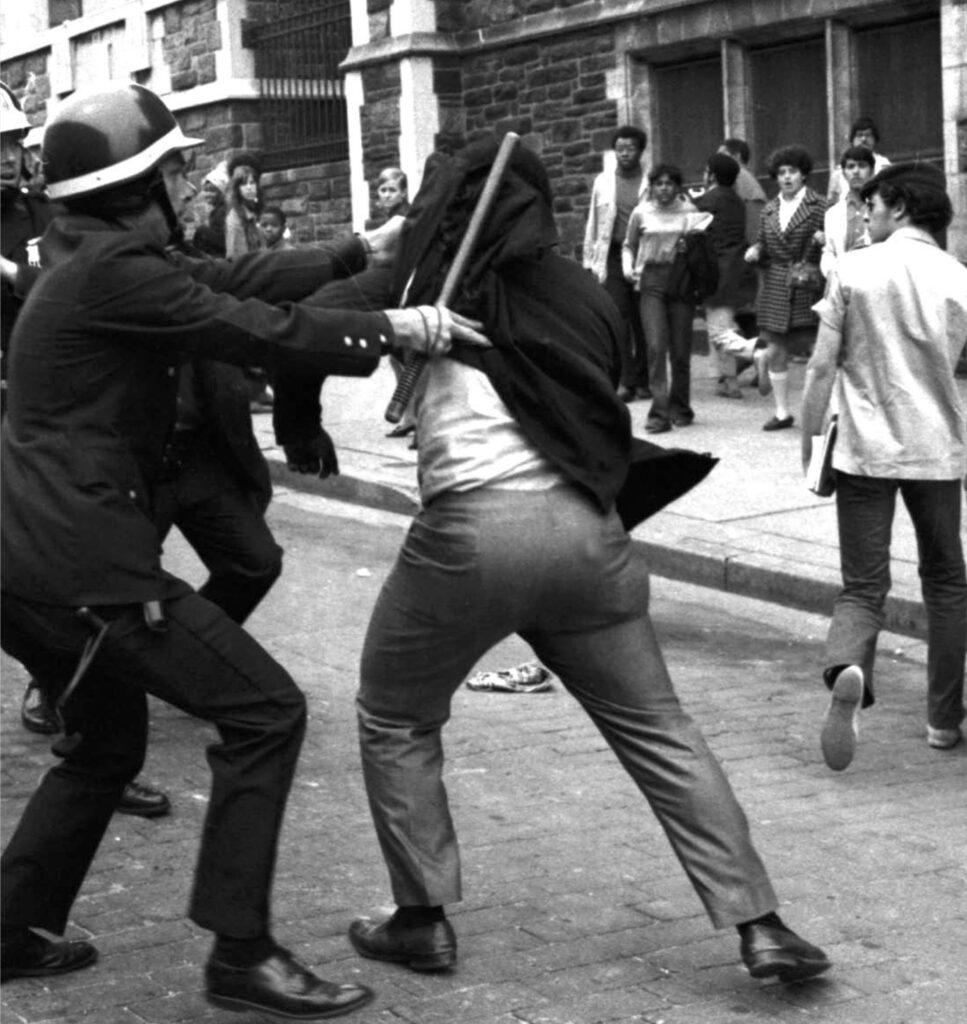

Even with these developments, student dissatisfaction continued, culminating on April 22 when the Black and Puerto Rican Student Community took over the South Campus for two weeks, preventing students from attending classes held there.

On April 28 President Gallagher told the faculty that the College would remain closed as long as necessary to reach a mutually satisfactory settlement of the Black and Puerto Rican Student Community demands. “Patience, dearly bought, must be the order of the day,” he declared.

Whatever immediate progress could have resulted from these negotiations was cut short when Mario Procaccino, one of the candidates in that fall’s New York mayor’s race, obtained a court order to re-open the college. The arrival of police on campus led to President Gallagher’s resignation. As he noted in his resignation statement: “… My own functions as a reconciler of differences and a catalyst for constructive change have become increasingly difficult to carry out. And with the intrusion of politically motivated forces in recent days, it has become impossible to carry on the processes of reason and persuasion.”

Source: Alia Ra’naa.

Even though these negotiations were incomplete, some of the results of these demands were seen on the campus within the next two years. In addition to the Spanish language requirement for education majors, courses in Black and Puerto Rican heritage, and greater student par- ticipation as noted above, a separate department of Urban and Ethnic Studies was established at the college in the fall of 1969.

Regarding the Fourth Demand, an immediate effect was the implementation of Open Admissions in 1970 rather than the original target date of 1975. But many of the issues of the Five Demands protest were addressed slowly and methodically only long after the protest ended.